In this post, you meet Raistlin Laplace. You will hear more of him at a later time. Please find the Finnish version here.

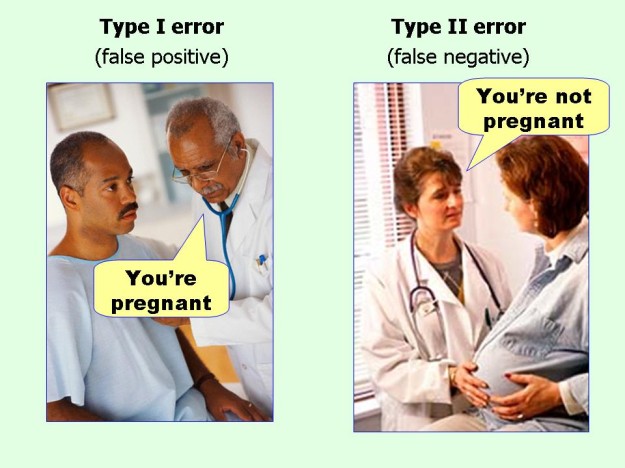

Raistlin Laplace has just received a diagnosis from his psychiatrist. It’s a sunny day of early spring, as he sits down on a bench in New York’s Central Park and opens an envelope. His thin lips hesitate upon the judgement held in his bony fingers: “Epistemological Hypersensitivity”. It had something to do with how patterns are distinguished from the midst of noise. Like how a radio tuned in the middle of two channels doesn’t tell much of the DJs’ music taste; too much noise, too little signal. The human brain is a signal detection machine without comparison, as it can detect satanic verses in backwards-played metal music or see Jesus in a dog’s anus (has happened). But Mr. Laplace’s problem was at odds with the one of those who seek secret codes in the bible. He was obsessed with avoiding randomness-created illusory patterns. The diagnosis made sense in a way, but he had long ago given up trust in things that made sense.

Raistlin spent his youth in a small town called Naples in southwest Florida. It had sounded aptly European to his French-Russian immigrant parents, who wanted to offer their only child a more tolerant environment from a less war-prone part of the world. It wasn’t immediately clear that Naples was, in fact, a red-neck village where parents spent most of their days commuting, and children in bloody fights with the youngsters of nearby villages.

Raistlin had always had a sickly appearance, although he was seldom ill. He had a feeble posture and pale complexion, combined with the contrast between his icy blue eyes and jet-black hair. This was more than enough to make the superstitious elderly whisper. Knowing this, and upon discovering the local library in elementary school, he realised he took great delight in the books found at the corner marked occultism. He devoured everything from shamanism to theosophy and new age. Sports—or, to that matter, anything else which interested other children—he couldn’t care less about. Having a hard time fitting in, he would’ve most wanted just to spend time alone with his books.

The first time his information universe collapsed was, when in junior high, he had to admit that the rituals and techniques of the occult-corner didn’t work as promised. Everything adults wrote wasn’t unerring; all information wasn’t knowledge. But the shock waned quickly and little did he know that this was only the beginning.

On a rainy New York day, 28-year-old Raistlin sealed the envelope containing a bankruptcy application of his startup company. He pondered on what had gone wrong. He had done everything right; read all the right books, followed the strategies of highly successful companies, listened to hundreds of hours of popular psychology-inspired sales training tapes, taken educated risks, and for years worked with a relentless, never-give-up attitude. At some point the money just run out and, as creditors breathed down his neck, more wasn’t coming. In the dim lighting of his studio apartment, Raistlin felt horror escalate. How could those writers, who so confidently spew out facts of the world, actually know how things truly worked? Were they really different than him, who—had any of the myriad small things gone differently—could now well be the CEO of a highly successful tech company?

He didn’t sleep that night. He watched an agonising replay of all those hours he had spent reading newspapers without learning anything about how the world actually worked. All the popular science news touting great new discoveries, all of which had later turned out to be premature. All the books written by those who thought their success was caused by their own actions and aptitude, instead of random occurrences of serendipity.

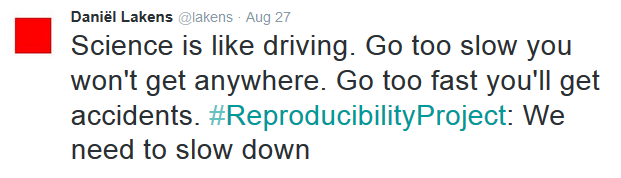

Two years later he only read peer-reviewed scientific journals. That is, until the discussion which followed mathematician-statistician John Ioannidis’ article “Why most published research findings are false” persuaded him of the fallibility of the scientific method (outside of physics, at least). The relationship between information and knowledge he had learnt about in junior high, began forming as an obsession: Raistlin wanted no more information, and he hungered for knowledge. Pure mathematics with it’s provable axioms finally offered just this, and our bony learning addict delved into it. By a stroke of luck and a relative’s recommendation, he ended up working in a bank. He vowed to avoid all information which wasn’t kosher; if the signal-to-noise ratio was low, the gates of his mind remained sealed.

This resulted in an unexpected problem: the more he aspired to isolate himself from “useless nonsense”, the more sensitive to it he became. On those few days he strolled outside, the shock headlines at newspaper stands turned his stomach to knots. Advertisements filled him with outrage. He also started avoiding social situations when he realised how easy it was for good stories to get stuck in his brain. He worked as a risk analyst, and didn’t want to start fearing airplanes just because some acquaintance of an acquaintance had experienced dread during an emergency landing. Compulsions—like fast repetition of names of old Russian mathematicians, when someone used anecdotes to advocate a position—got worse and eventually his worried employer steered him towards professional help.

Rays of intensifying sunlight warmed up Raistlin’s bench and whispered promises of summer to the people wandering about Central Park. Raistlin had promised his psychiatrist to begin participating in a therapy group. The anxiety meds he took had also started to kick in, which made him buy a newspaper from a nearby hot dog stand and even read a couple of pages. It didn’t feel as bad anymore, perhaps about as sensible as his diagnosis. The psychiatrist had explained that epistemological hypersensitivity meant anxiety stemming from the origin of knowledge. That there wouldn’t be a signal in the noise. Fear of realising, upon the moment of one’s death, that he had spent his life reacting to ghosts the mind saw in the noise, instead of real phenomena.

Some hours later, a young student walking a dog in the park, to her delight stumbled upon a pristine newspaper. She took it home and opened it in front of a bowl of cereal. At first glance, the paper looked untouched. Only after reading several articles, she noticed some very small but resolute handwriting. In the margins, someone had written: “Kolmogorov. Kolmogorov. Kolmogorov.”